Fundamental elements of drawing

A line is a dot that went for a walk.

Paul Klee (1879-1940)

The fundamental elements of drawing are:

- point

- line

- tone

- unmarked areas

These elements may be combined in limitless ways to represent objects and to express relationships. Through making marks on a flat, two-dimensional plane we can convey real and imagined things and events in spatial and temporal dimensions. Portrayal of things in their wholeness, in their parts, and in combinations not seen in the real world is possible with drawing. Through the qualities of marks we can also convey feelings and evoke emotional states. We can even synaesthically conjure sensations and phenomenological responses normally associated with senses other than the visual.

As the draughtsperson casts points, lines and tones onto the field defined by the initially blank paper, any human observer cannot resist but to perform visual operations that engage their psyche to interpret them. Relationships between figure and ground are called into question to be resolved. Depth cues are interpreted. Patterns beg for recognition. Shapes and forms are imagined from outlines (and hints gained from the relationship between those outlines and spaces and blanks), and from areas of tonal mass and from gradations in tone. Motion, kinesthetic relationships, textures, and indeed the whole gamut of physical conditions may be expressed through the juxtaposition on the drawing surface of points, lines, chiaroscuro and their opposite - blank space!.

Lets take a closer look at ech of these fundmental elements.

Point

Writing teaching material intended for first year students at the famous German Bauhaus Weimar School in 1926, Wassily Kandinsky had the following to say about the point.

The point is the result of the initial collision of the tool with the material plane, with the basic plane. ... The basic plane is impregnated by this first collision. ... The invisible geometric point must assume a certain proportion when materialized, so as to occupy a certain area of the basic plane. In addition, it must have certain boundaries or outlines to separate it from its surroundings.(Kandinsky 1926, p28)

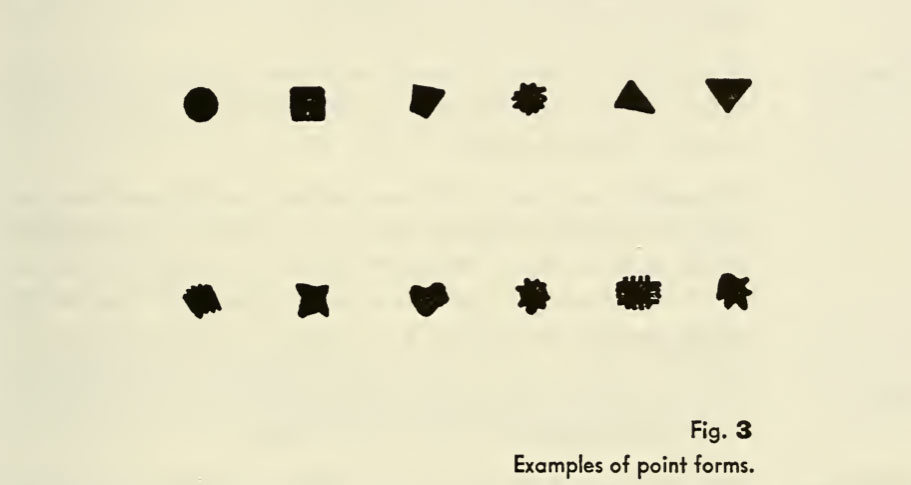

Externally, the point may be defined as the smallest elementary form, but this definition is not exact. It is difficult to fix the exact limits of the concept "smallest form". The point can grow and cover the entire ground plane unnoticed‚ then, where would the boundary between point and plane be? (29)

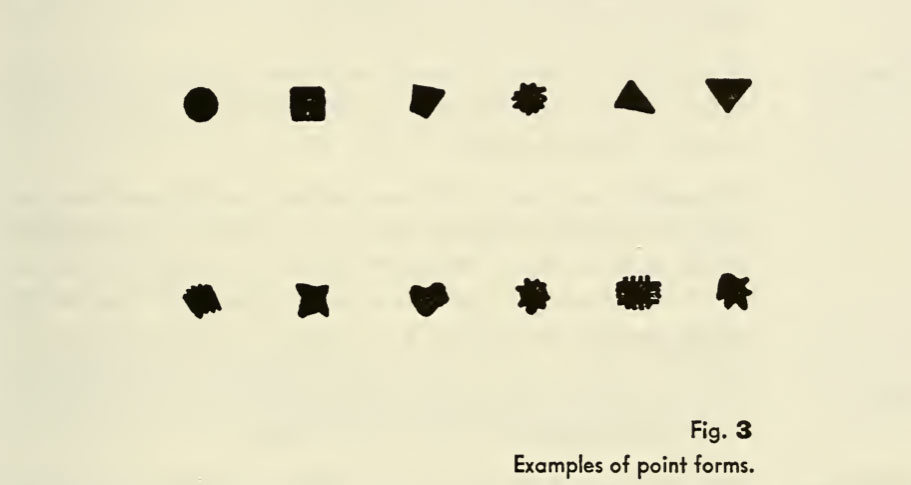

In its material form, the point can assume an unlimited number of shapes: it can become jagged, it can move in the direction of other geometric forms, and finally develop into entirely free shapes. It can be pointed and tend towards the triangular. Or, prompted by an urge for relative immobility, it can take on the shape of a square. When it has a jagged edge, the elongated projections can be of smaller or larger size and take on a relationship to one another. Here no boundaries can be fixed and the realm of points is unlimited. (30-31)

The point digs itself into the plane and asserts itself for all time. Thus it presents the briefest, constant, innermost assertion: short, fixed and quickly created. (32)

The point is temporally the briefest form.

In theory, the point, which is

1. a complex (size and form) and

2. a sharply-defined unit, should constitute to some degree its relationship with the basic plane as a sufficient means of expression. (35)

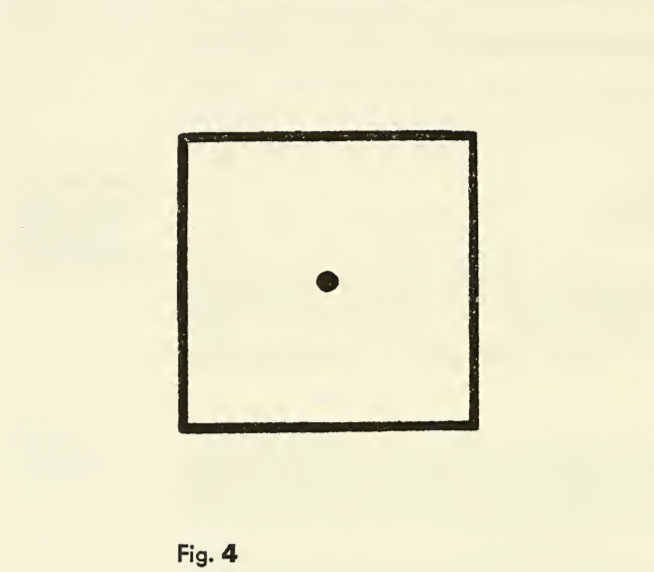

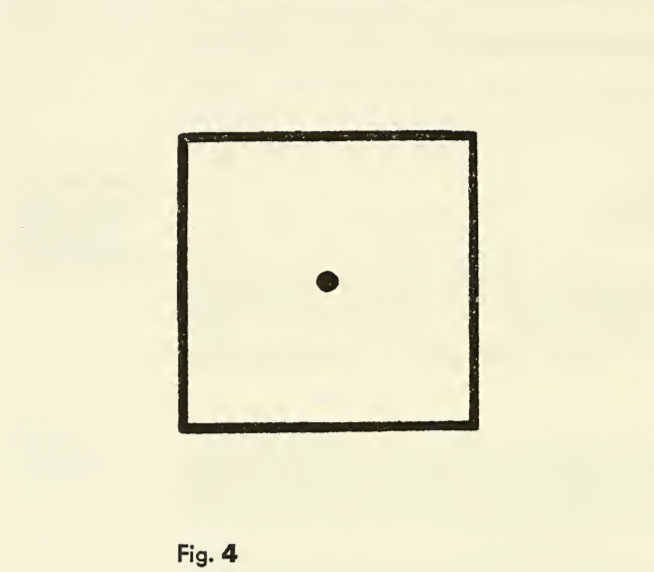

The simplest and briefest [case of the point] is that of the centrally-placed point - of the point lying in the center of a surface which is square in shape.

This, therefore, represents the prototype of pictorial expression. (36)

Kandinsky goes on to talk about the relationship between the point and the line.

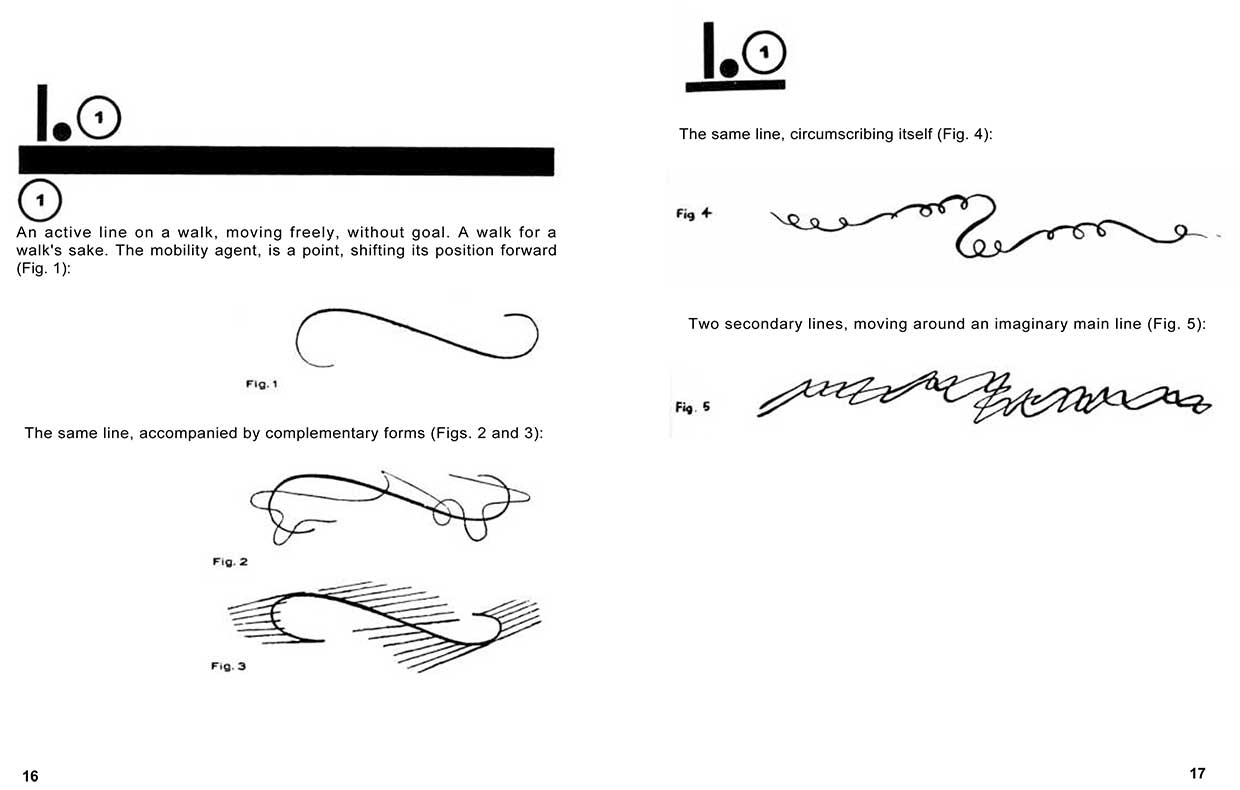

There exists still another force which develops not within the point, but outside of it. This force hurls itself upon the point which is digging its way into the surface, tears it out and pushes it about the surface in one direction or another. The concentric tension of the point is thereby immediately destroyed and, as a result, it perishes and a new being arises out of it which leads a new, independent life in accordance with its own laws. This is the Line. (54)

Line

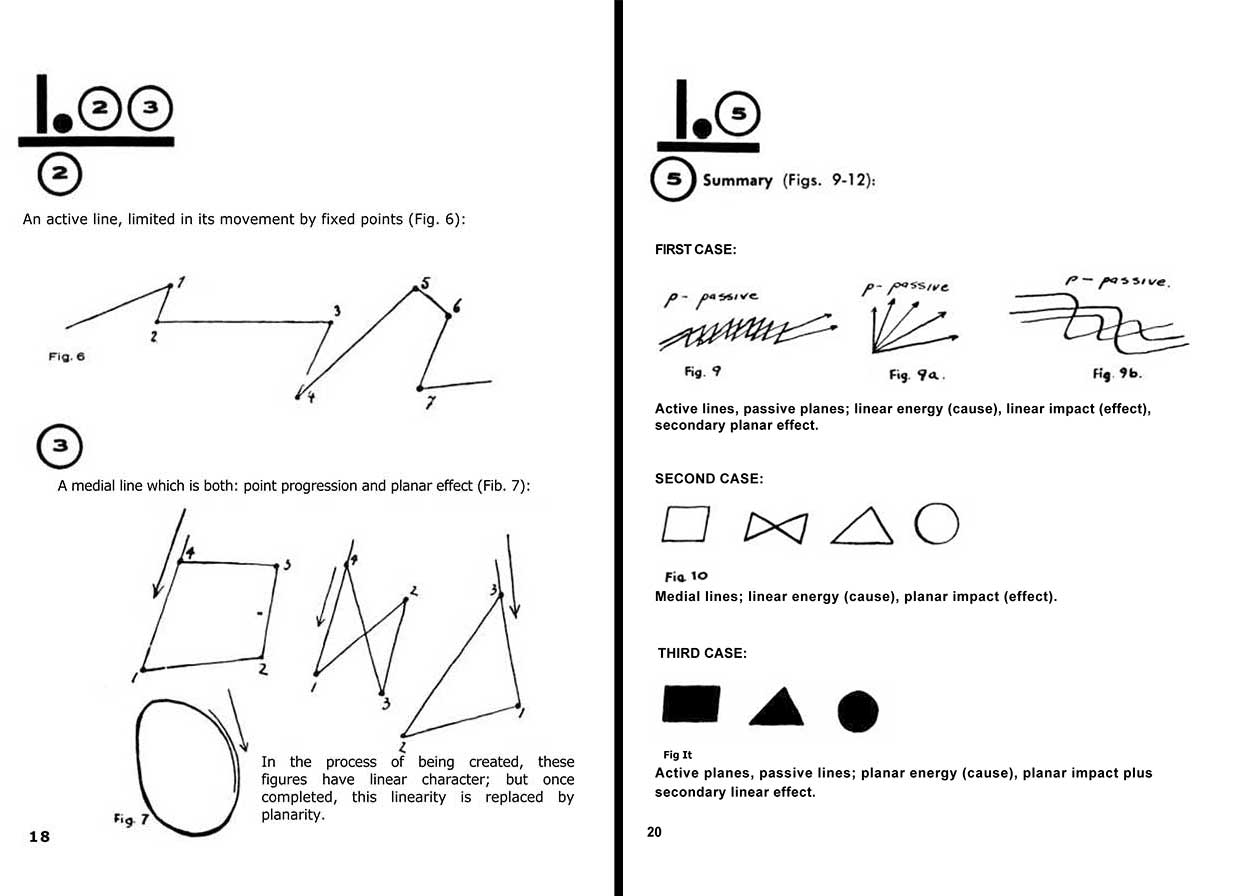

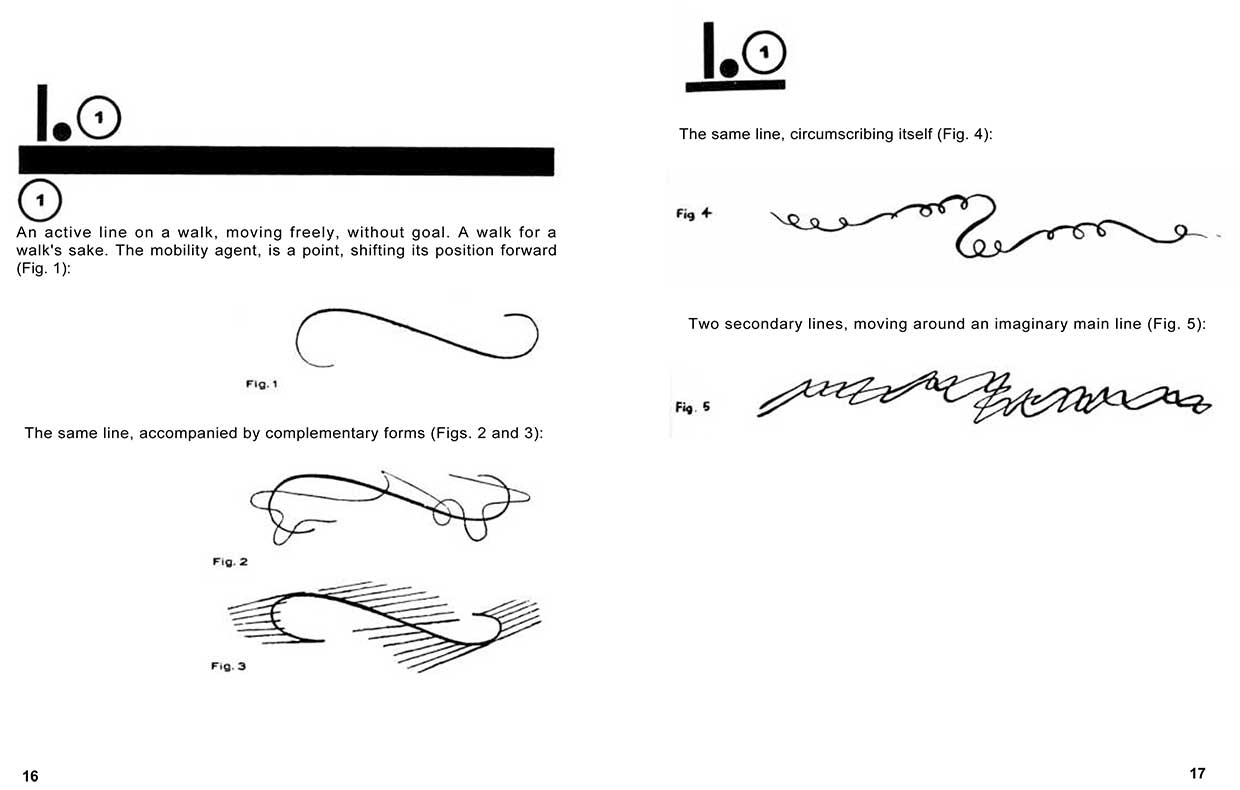

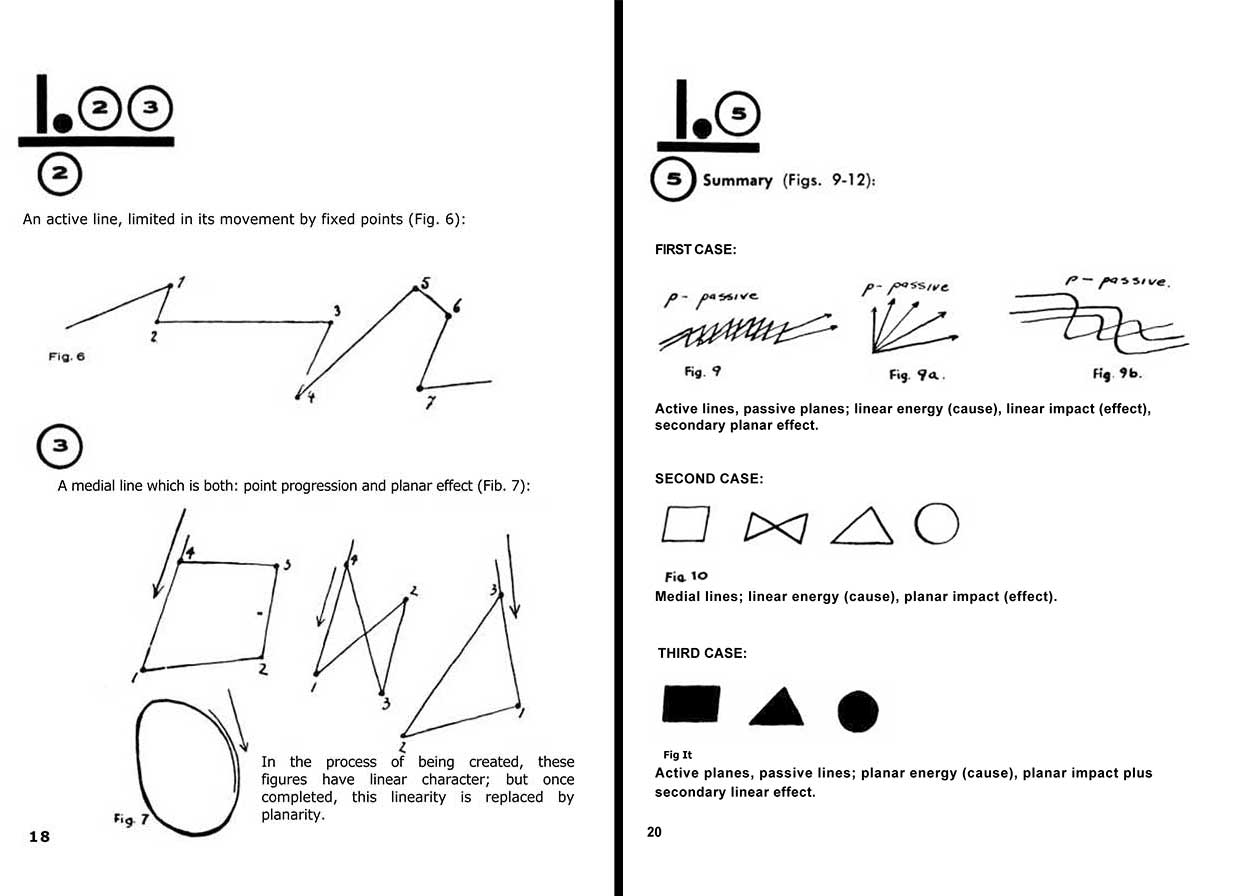

Another artist who taught at the Bauhaus school and whose name and artwork may be familiar to you is Paul Klee. The following is a series of extracts from notebooks he used to teach foundational students. He outlines the dynamic qualities of line and how lines can create planes and so lead to the representation of other dimensions on the 2D paper plane.

(Klee 1925, pp16-20)

In a more contemporary book, Drawing, a creative process, which is highly recommended reading, Francis Ching describes drawing as “dragging or pulling a tool across a receptive surface.”

Reflecting what Klee demonstrates in the above excerpt, Ching says further:

Once a line is drawn, it exists as a static element, fixed in space, but the kinetic nature of its creation continues to reveal itself to the eye. A line not only describes shape and structure, but also expresses the pace, rhythm, and cadence with which it was drawn. It can be bold or delicate; it can swell or taper as it rises or falls; it can be dense or lightly textured as it skips across a textured surface. We can read into these qualities the skill of the hand and the intent of the maker. (Ching 1990, p20)

Tone

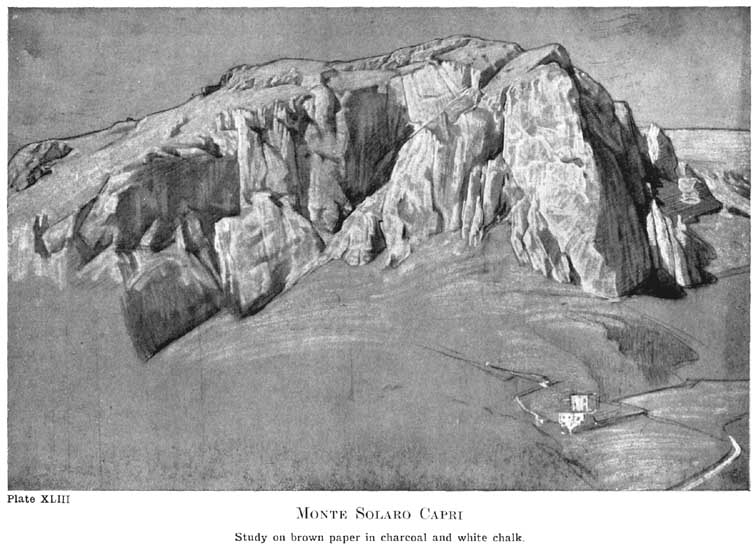

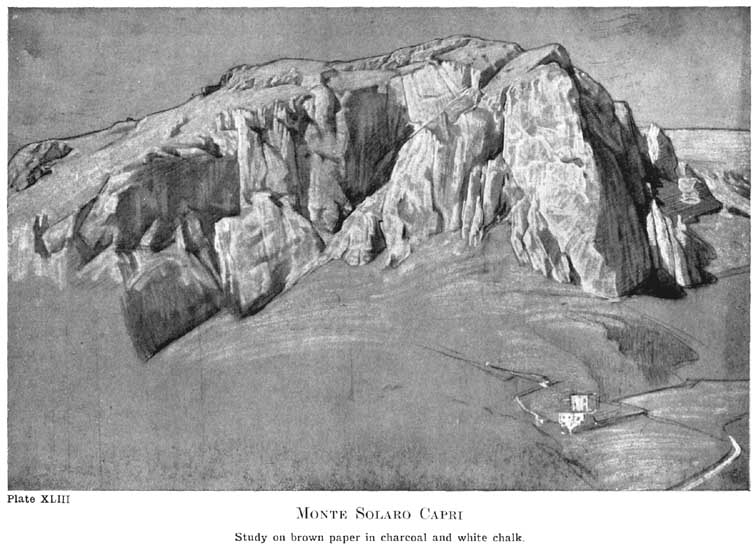

Tonal rendering contributes very much to the portrayal of mass, form and texture. Areas of light and shade and the transitions between them can be simulated. The Speed drawing below was prepared on a paper that already had a tone to it. Both the shadow areas and the highlights have been added to the ground (the background surface) to convey the forms of the mountain.

Source: Harold Speed, The Practice and Science of Drawing, (Seeley, Service & Co, London, 1913), 189.

Unmarked areas

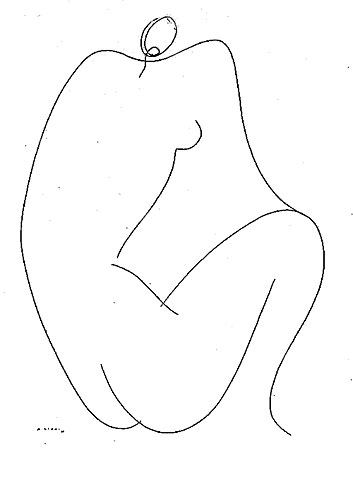

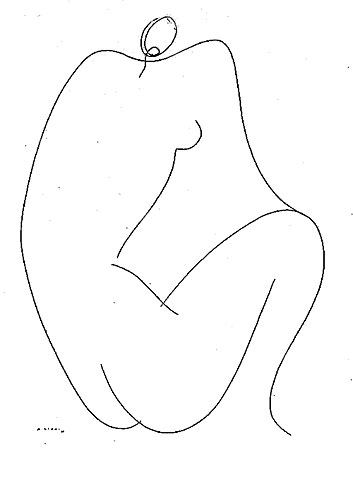

In simple line drawing, a proficient artist may force the viewer to interpret the blank areas as voluminous forms without the aid of any shading whatsoever.

Alberto Viani (Quistello 1906) Figure Pen and black ink; 695 x 491 mm. Venice, private collection. Source: Pignatti, Terisio, Master Drawings: From Cave Art to Picasso, (Evans Brothers, London, 1982), 366.

Another phenomenon related to the way lines can work in drawing concerns a psychological visual affect that is referred to as 'closure'. Closure has a lot to do with our perception of patterns and our tendency to cognitively complete them when parts appear to be missing. What this means is that during visual perception we may assume a structure or a virtual relationship even when there is none directly represented. Whilst this could work against one in a drawing, if an unintended virtual structure were to dominate over an intended one, in many instances closure is used to make a drawing more interesting and to engage a viewer in the synthesis of meaning. In such cases unmarked areas are used to imply lines and shapes and to activate the figure-ground relationships created by positive and negative shapes.

Developing skill with drawing fundamentals

According to Betty Edwards, the five most important skills to learn in relation to drawing are:

- how to perceive and draw edges

[e.g. the shared edges of contour drawing – see week 3 tutorial]

- how to perceive and draw spaces

[e.g. negative spaces – see week 4 tutorial]

- how to perceive and draw relationships

[e.g. perspective and proportion – see week 5 tutorial]

- how to perceive and draw lights and shadows

[e.g. shading – see week 7 tutorial]

- how to perceive and draw the whole of your subject

[i.e. the overall character, its “thingness”, or gestalt – see week 6 tutorial]

(adapted from Edwards, 2008, pp96 & 163).

Qualities of line

Refer to the Edwards text, p. 25 for examples and descriptions of unique line qualities. She refers to examples:

• The ‘bold’ line

• The ‘broken’ line

• The ‘pure’ line

• The ‘lost-and-found’ line

Qualities due to the drawing implement and the drawing surface

The video by Leonardo Pereznieto in last week's 'related links' demonstrated very effectively the different qualities of a variety of drawing implements. He also showed how the drawing surface itself will affect the quality of the line. In the materials list you have been asked to purchase pencils of a range of hardness, a graphite stick, conté chalk and charcoal sticks. When you experiment with each of these implements on smooth paper such as newsprint and on more textured paper such as your sketchbook you will observe some of these different characteristics. There are different qualities of line that may be achieved through purposefully using drawing implements in different ways. For example, a sharp pencil lead produces a finer line than a blunt one; using the sharp point or the flat edge of the lead produces different marks. The pressure that is applied to the implement influences the line weight and character. In addition to pencils and graphites there are many kinds of pen that may be used.

In another video in this week's 'related links' by Leonardo Pereznieto demonstrates how qualities of line and tone achieved with different impliments and techniques as he draws a glass of water.

Expressive qualities

As previously described (Lecture 1) our visual perception and cognition consists of physical, psychological and cultural aspects. All of these contribute to how and what we see. When we draw, unless we are purposefully incorporating symbols with codified meaning, generally we are communicating using marks that may be quite fluidly interpreted. The lines and tones that we create when drawing combine to convey meaning in ways that do not usually have strict rules associated with them. Some are kind of ‘felt’, through the way in which our visual sense overlaps and feeds into our sense of touch – as in texture. Some feed into our sense of space, kinesthetics (movement) and direction – as when a line starts off thicker and then trails off to nothing. Some help us define surfaces, shapes or shadows - as in cross-hatching. Some lines and shapes work on our mental engagement with and anticipation of pattern and rhythm. And some lines invoke emotional responses that may vary from individual to individual and which may arise from memory-based associations.

Stylistic qualities

The way in which lines are used when creating a drawing can portray characteristics which, when they are consistently achieved, are often referred to as a style. An experienced draftsperson can develop this kind of consistency so that what they produce can be readily recognised as being uniquely attributable to them. Style can reflect an attitude, a typical approach or point of view, or a way of seeing. Sometimes typical choice of subject matter can contribute to identification of style. Style can also refer to purely formal aspects such as the way shapes are used to construct form. Other technical qualities such as the quality of line used, or maybe a particular manner in which cross-hatching or shading is achieved contribute to style. More often than not, all of these attributes contribute to what we recognize as a personal style. On p. 24 of the Edwards text there are two drawings of the same subject which serve to highlight the personal stylistic differences of the two artists.

Style can also refer to a consistency that may arise from a particular school or class where a particular artist, or group of artists, exerts a strong influence on others.

More drawing basics

Contour Drawing

An approach to contour drawing is described in the Edwards text (pp: 88-113) and the tutorial exercises for week 3 are concerned with this technique. The basic idea is to establish the edges that will represent shapes that stand in for forms that you observe. This sounds easy when described as such but one quickly finds that issues regarding how much detail, and what to do about soft edges and so on make things more complex. One needs to decide what is important. And this usually relates to… some of you may already have guessed… the context. What is it that you need to highlight to achieve your objective? Then, of course—beyond contour drawing exercises—after one decides what is important one will need to decide what to do with the rest!

Gesture drawing

The term ‘gesture’ is applied to a style of drawing that goes one step beyond establishing the contours of the subject. Don’t forget that we are still talking about basic line techniques here and not about tonal drawing or any type of more formal hatching or shading. Gesture drawing is a step beyond establishing the contours or outlines, towards additionally conveying the form and mass of the subject using lines. The technique often resembles a kind of scribbling where the directionality of a line and its connection with other lines provide a scriptonic account of basic forms. This basic form can be enhanced variations in density of line provide emphasis.

Calligraphic drawing

Once again here we are referring to a style of drawing that expresses form without emphasizing the tonality. Most often when we think of calligraphy we think of a very formal and fluid form of handwriting. In drawing, calligraphic line may be used to account for dominant edges, for three-dimensional form as shapes and also for movement. With calligraphic drawing there is a concern for the expressive quality of each individual line. Calligraphic lines are often achieved using an ink loaded brush or variable pen nib. Each line contributes to an account, not only of the form but also of other more emotive and/or cognitive qualities, purely through variation of line width, the textural quality of the line and the varying directions of lines—all of which may also be interpreted as the ‘movement’ of the lines. Especially in the ancient traditions of China and Japan, the calligraphic art style is respected in a sense that Westerners might refer to as ‘poetic’ or even meditative.

Structural lines

Lines are also used in a number of different ways to formulate dimensions, proportions, compositional structure, spatial relationships and perspective. When they are used in these ways, they may only be lightly sketched and drawn over, or even temporarily applied. Sometimes they remain as part of the finished work. Sometimes they are not actually drawn but still kept in mind as the composition is formulated and so will still give rise to the drawing’s structure. Most often, structural lines are used as a subtle means of organizing a drawing. However, especially in the case of diagrams, they may also play important roles such as framing, dividing sections and showing: measurements, fields, layers, movements, directions, relationships, and to outline shapes that describe abstract concepts.

Style as fashion, and genre

Often when viewed in the historical sense, but also recognisable contemporaneously, style can be associated with a particular period or fashion. For example, the unique drawing personal drawing style of Aubrey Beardsley is may be broadly associated with the Art Nouvaeu style which is recognised as a fashion arising from a historically defined period, the early 1900s.

In a related but slightly different sense, style is also an attribute that may be useful in defining a genre. Genre is a term that we use more and more these days when referring to classes or groups of works associated through characteristics that combine to create a particular sense of cultural identity. In this sense we can say that certain technical and contextual aspects contribute to a recognizable style and when various examples of the style begin to comprise and identifiable cultural subset it may be called a genre.

The word style is used flexibly in ways that combine all of the aspects considered above. For example, when we refer to Manga as a cartoon style of drawing we mean that it is recognisable through technical characteristics such as the particular way the figures are typically constructed by defining their outlines with a certain quality of line work. We can say that the style is recognisable also because of the way idealised or conventions of shape and form rather than true-to-life or realistic proportions are used to represent faces and bodies and that this is generally so with cartooning. The often flat use of colour and the particular range of colours used is also a stylistic attribute. These are some of the qualities that enable us to classify Manga as a cartoon style, but Manga is also referred to as a genre. In this sense we tend to consider the social and cultural background such as how the Manga style evolved in Japan; who the audience is; typical storylines, subject matter and character types; how Manga is consumed in defined media markets such as print, movie and games; its spread as a fad or fashion through global culture; and, the emergence of further identifiable subsets or sub genres of Manga. Further, a follower or fan of Manga will readily recognize the style of a particular Manga artist through the unique, ‘trademark’ traits identifiable in their work. Through the example of Manga we can see that when referring to drawing and illustration, style is a word that is used to classify art in terms of context, technical qualities, genre and, in terms of the unique qualities attributable to an individual or school.

The relationship of style to purpose and intent

There was a time when drawing was the fundamental means by which a record of an event, a scene, an object, person or any other living thing could be obtained. In those times, more people would draw as a part of their regular note taking, diary records and letter writing. The skill of drawing was important in many trades and professions. Early scientists would sketch records of their observations. Explorers sketched in their travel diaries. Artists were hired to record official happenings and produce family portraits.

In the past there were also particular skills required to produce drawings in a form that could be reproduced as multiples via printing process. The woodcut, the etching and the lithograph are examples of these techniques, which essentially were ways of drawing onto a durable surface that could be inked so that multiple copies of an original could be duplicated onto paper. These days most image recording and reproduction is achieved by photochemical, photomechanical and photodigital process. One notable exception is the role required by quirk of the legal system: that of the court artist. There is also a continuing tradition whereby artists are sent to record war and humanitarian efforts involving our armed forces. In these instances it is the ability of the artist to be selective and to interpret as well as to represent that makes their contribution significant over photomediated records.

Generally speaking, it is in situations where these factors – selection, interpretation and representation – are important that drawing maintains an active role in contemporary communication design, development and production. In relation to typical contexts and specific communicational channels where drawing is used, there are conventions that indicate the appropriateness of particular styles for particular purposes. Whilst working outside of these conventions may sometimes be a creative option and may in some instances achieve a communication objective, it is more usually the case that working outside of the conventions means the drawing is not taken seriously, taken too seriously for its context or, does not communicate effectively. In other words, how a drawing is treated is part of its message. In fact, the approach, the stylistic considerations, the context and the purpose all influence what is commonly called the graphic treatment. When drawing for commercial application the choice as to appropriate graphic treatment will be a primary one.

In the multimedia context it is common to refer to a particular category of visual communication with its unique characteristics as a 'channel'. The following table correlates some examples of channels of visual communication where drawing skills are usually involved with: the purpose; some typical contexts; typical stylistic considerations; and, the main factors in consideration in the approach to drawing for application in that particular channel.

TABLE 1: Some channels of visual communication correlated with: the purpose; some typical contexts; typical stylistic considerations; and, the main factors in consideration of the approach.

References

Ching, Francis D. K., (1990) Drawing - a creative process, John Wiley & Sons, Inc

Edwards, Betty, (2008) The New Drawing on the Right Hand Side of the Brain, Harper Collins.

Kandinsky, Wassily, (1926) Punk und Linie zu Fläche, Walter Gropius and Lazlo Moholy-Nagy, eds. English edition, Point and line to plane, Dearstyne, H. and Rebay, H., trans. (Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation. New York, 1947).

A pdf of the 1947 edition is available here: http://ia700608.us.archive.org/8/items/pointlinetoplane00kand/pointlinetoplane00kand.pdf .

Klee, Paul, (1925) Padagogisches Skizzenbuch, Walter Gropius and Lazlo Moholy-Nagy, eds. English edition, Pedagogical Sketchbook, Sibyl Maholy-Nagy trans, (Frederick A Preager, Inc., New York 1953)

.

A pdf of the 1953 edition is available here: http://www.blog.desarte.com.br/attachments/302_Paul%20Klee%20Pedagogical%20Sketchbook.pdf