The paradox of print cartoons

Historians of art have not paid much attention to the cartoons we find in the print media. They are ephemeral products created quickly; today’s cartoon will be trashed with tomorrow’s paper. Yet they often involve great ingenuity and help reinforce (or unsettle) the opinions of thousands of readers. Some are excellent examples of graphic art, yet often they are just a vehicle for ideas conveyed by written words. More than most graphic art, they directly engage with actual people and events, yet do so by resorting to non-realistic modes of representation. We can learn a lot about the potential of the drawn image, and its relation to words, by reflecting on cartoons.

Kinds of cartoons

Originally ‘cartoon’ meant something rather different: a preparatory drawing for a serious artwork. Nowadays a cartoon is a simple drawing which offers a comment, usually humorous or satirical. Single panel cartoons can be classified as ‘gag’ or ‘editorial’; the latter (sometimes called ‘political’) are normally found in the ‘op-ed’ (opinion-editorial) pages of newspapers. Multiple panel drawings are usually called ‘comic strips’. However it is worth noting that some of these, such as Doonesbury, involve acerbic commentary on current affairs in similar fashion to editorial cartoons. A self-contained editorial cartoon offering its own comment on the news can be distinguished from a caricature or other drawing commissioned as an illustration to accompany some written piece on the op-ed pages.

Historical development

The cartoon is a child of the printing press, which was developed in Europe in the mid-fifteenth century. Before newspapers as we know them existed, printed images were used in political pamphlets for purposes of ridicule. The eighteenth century, when printed periodicals became part of western European culture, was a time when satire flourished. Modern cartoons are mild and polite compared to many published in earlier times when newspapers and magazines tended to be more partisan in their political stance. In times of war cartoons depicting the enemy were especially derogatory, and crude stereotypes of despised minorities have also been prevalent. Modern cartoons tend to use the medium in a more sophisticated way, relying less on cumbersome allegories and explanatory text.

Apart from printing, which delivered a mass audience, and growing political turbulence from the time of the Reformation, how can we account for the emergence of the cartoon? At least until modern times, one reason for including cartoons in a publication was to cater for the many who could not read. Nowadays nearly everyone is literate but a cartoon can be scanned in much less time than it takes to read an editorial or opinion column. Furthermore, readers are grateful for a graphic image that ‘breaks up’ blocks of text on a page, and the presence of a cartoon signals that here is a bit of fun.

European medieval art helped prepare the way for the cartoon. It was normally allegorical. A painting had some religious message to convey. Even if purely aesthetic considerations motivated the artist or satisfied the viewer, art had to observe the conventions. Pictures would include a lot of symbolic iconography: for instance the infant Jesus would be shown handling some object shaped like a cross, indicating his destiny. Or an animal might be included in a picture because the viewer would understand it to represent one of the Seven Deadly Sins relevant to the subject (the sin of envy was represented by the dog; the sin of gluttony by the pig). Cartoonists were able to utilise the techniques of allegory and symbolism. They still use them. A favourite medieval subject was St Jerome. Paintings of him always included a lion because of a story that he once removed a thorn from the foot of a lion. Now exactly the same principle applies when contemporary Australian cartoonists routinely depict the federal politician Tony Abbot wearing boxing gloves. He distinguished himself as a boxer at university. In each case the visual reminder of a biographical event helps identify the person. The lion or the boxing gloves also serve to suggest something about the character of the person. The saint is selfless, ready to risk his life to help a creature in distress. The politician, it is implied, has a pugnacious style—he is more ready than most to adopt an aggressive approach.

Medieval art contributed more than technique. As an earlier lecture pointed out, the art of any period derives from a certain world view. In the Middle Ages Europeans conceived of the world as ordained (not random), ordered (not chaotic) and hierarchical (not egalitarian). Although they did not necessarily trust surface appearances, they did believe that all things and persons had a fixed definite nature and that there were all kinds of correspondences between things in the world. It was meaningful to draw analogies between, for instance, God – a king – the father of a human family – the lion as ‘king’ among beasts. There was a quaint belief that for every animal found on land, there must be an equivalent creature living in the sea (elephant = whale and so on). So to explain a person or thing, it was natural in medieval times to do so by drawing attention to its known relationship, or its similarity, with some other thing in the world. Our world view may be very different but if you want to draw a cartoon, it may help to think of analogies. If the person was a bird, what kind of bird would he or she be? If you have to draw an animal think about what kind of machine it would be. And vice versa.

Pieter Bruegel, the Elder, Big Fishes eat Little Fishes, pen drawing, 1556

Something else helped in the development of the cartoon: the emergence of caricature as an approach to portraiture. The word comes from the Italian for ‘exaggeration’ and was first used by Annibale Carracci in the 16th Century. He asserted that exaggerating some defect or deformity was the best way to capture the subject’s true character (Rhodes p 14). The Platonic philosophy popular in the Renaissance held that earthly things were poor imitations of transcendent ideal forms. Hence the more you made someone look beautiful the more they would resemble universal Beauty rather than themselves. What gave people their individuality was their deviation from the ideal (Rhodes p 15). This fitted well with the medieval confidence that everyone had a fixed nature that would reveal itself in one way or another. Caricature became an important cartoon technique, and more will be said on the subject presently.

When new techniques allowed the printing of photographic images, drawn illustrations largely disappeared from newspapers but cartoons survived. In the 19th and 20th century cartoons they were adopted by newspapers all over the world, although in some countries cartoonists still have to tread carefully. The middle decades of the twentieth century were perhaps the golden age of the cartoon. Sophisticated gag cartoons enlivened the pages of periodicals such as the satirical magazine Punch in the U.K. and The New Yorker and Saturday Evening Post in the USA. In the 1970s the satirical edge of the ‘counter culture’ breathed new life into the form (e.g. in Australia Michael Leunig and Patrick Cook emerged in this period); meanwhile ribald and irreverent ‘underground comics’ took the comic strip into new territory. Australia, incidentally, produced a disproportionate number of talented cartoonists through the 20th Century, just as now we seem to have some very talented cinematic animators. By the last decades of the century, the number of newspapers in western countries had declined significantly and fewer cartoonists were employed, with more papers relying on the purchase of syndicated cartoons. This has meant less attention given in cartoons to issues of local—as opposed to national—interest.

Relations with other media

There has always been a lot of cross-fertilisation between popular arts. Before the 20th century, live theatre—for instance the allegorical tableau, the interchanges of vaudeville comedians—was an influence on cartoons. By the early 20th century new genres such as comic strips were evolving and before long new media: film and later television allowed animation of drawn characters. In Australia Leunig’s cartoons have been turned into a stage play and there are films and television series inspired by cartoons (The Adams Family, the St Trinians films) as well as the blockbuster movies based on comic books. Some decades ago Mad Magazine flourished by publishing send-ups in strip form of well-known movies and TV shows (it still exists but its quality has declined). Interestingly, screen animation is no longer confined largely to slapstick comedy, fantasy and children’s fare; shows such as The Simpsons and South Park can involve quite sophisticated social satire in the manner of Doonesbury, Biff and other ‘intellectual’ cartoons and strips. On the other hand, attempts to replicate the editorial cartoon on radio and television current affairs have been few. Rubbery Figures, which used puppet caricatures, was more successful than the more recent weekly segment on ABC television’s 7.30 Report using the live actors John Clarke and Brian Dawe.

The cartoonist’s conceptual toolbox

Now let’s consider the techniques that the editorial cartoonist can use to make some comment on current affairs. The fundamental challenge is obvious: if I use words I can express some proposition. Here is an example: “Australia should restrict imported goods to protect the jobs of factory workers.” If I can only use an image I can at best imply that this is what I believe. A proposition can be abstract and general, effortlessly referring to a whole nation (with all its laws and procedures relating to import regulations) and all the thousands of people employed in manufacturing. An image has to represent something (real or imagined) in the world; it is inevitably concrete and particular.

Images can provide a great deal of detailed information while remaining quite ambiguous. A very realistic photograph of workers who have lost their jobs may establish that they are upset but still does not make the connection between the factory closing down and competition from cheap imports. Nor does it generalise the problem to other factories across the nation. Perhaps images on their own could do the job if we made a very long silent movie (or equivalent comic strip) that provided an exhaustive narrative, but that would be tedious and can not be done in a single panel. What does the cartoonist do?

Well, words may have to be retained in some way—at least in a brief caption or title. Beyond that, the cartoonist will have to make some departure from the complex and literal actuality of the situation. We can call such a departure a trope. In the first place, it will help to have representative characters: some typical worker who stands for everyone whose job is at risk. A character or symbol representing the nation might also help. The figure of Uncle Sam is routinely used to represent the USA, John Bull to represent Great Britain. This is the trope of personification. A century ago, the newly-federated nation of Australia was sometimes portrayed as an innocent young maiden stepping out into the menacing world.

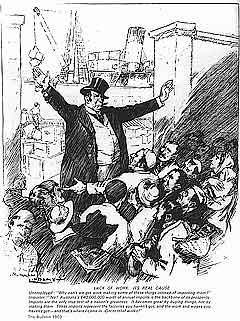

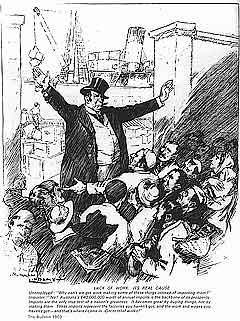

Rather than a whole narrative, a single dramatic scene implying a longer narrative is needed. A 1903 cartoon by Norman Lindsay from the early 20th century addresses this issue of ‘free trade’ versus ‘protectionism’, one of the most controversial of the time. A crowd of working people are pleading outside a dock with a prosperous looking ‘importer’. He has a top hat and cigar, conventional signifiers of ‘big business’. In the background a ship is being unloaded. The cartoon depends on lengthy dialogue printed below the image. The ‘unemployed’ ask ‘Why can’t we get work making some of these things instead of importing them?’ The importer’s contemptuous answer goes on for four lines. On one level the scene is realistic (allowing Lindsay, an artist of some renown, to deploy his drawing skills) but there is still a departure from actuality. The scene is a fiction; it did not take place and the importer’s arrogant words are implausible.

Norman Lindsay, "The Protectionist Case", The Bulletin, 1903

A cartoon from 1895 departs further from realism. It shows a worker being crushed in a press operated by a fantasy figure, an ogre labelled ‘Capitalism’. The worker tries to save himself by propping up the top plate of the press as it descends on him with pieces of wood labelled ‘trade unionism’, ‘co-operation’ and ‘Factories Act’—they seem pathetically inadequate. This is allegory: a range of political / economic phenomena have been systematically transposed into other, more tangible, terms in an imaginary narrative.

Artist not known, "Our Industrial System", The Bulletin, 1895

While modern cartoonists prefer to avoid inclusion of lengthy speeches or allegories requiring a lot of labels, they continue to depart from the real in one way or another. Tropes include the following:

- analogy and metaphor (implicitly comparing one thing with another in respect of some quality);

- metonymy (using part of the whole or an associated thing—e.g. a gun representing all the armed might of a nation);

- hyperbole (overstatement);

- strange juxtapositions and combinations;

- symbolism and allegory; personification;

- typology (using supposedly representative types);

- allusion (making connection to other texts).

In the first place, this is done to overcome the problem of images being inherently ambiguous. There are other reasons: transposing or transforming actuality can be a way to intensify comic or satiric effects.

The reader needs to grasp quickly what is going on in a cartoon. This explains the use of iconography like the following:

- Teachers are always depicted wearing academic gowns and carrying canes

- Scientists have white coats and thick spectacles and carry clipboards

- Greenies have beards and look scruffy

- Burglars always wear masks and striped jerseys.

None of this necessarily reflects reality. Depicting a classroom situation in a way that allowed the teacher to be identified as such without the iconography would be time-consuming and inconsistent with the spirit of subversive fun that probably motivates the cartoon.

The imaginative transpositions are meaningful because they invoke something already familiar. For instance to make the point that a politician is being alarmist without reason, he or she could be represented as Chicken Little who went around crying out ‘the sky is falling!’ This is metaphor (politician compared to Chicken Little) and allusion—which means making use of, or reference to, characters or situations from well-known stories, fables, movies, art works and so on. Here are some more examples, all of which have been utilised in cartoons again and again:

-

Noah’s Ark

- King Kong on the Empire State Building

- The seven dwarves

- Romeo & Juliet

- The hare and the tortoise

- The emperor’s new clothes

- Frankenstein’s monster

- Adam and God touching fingers (from the Sistine Chapel)

- The Three Wise Men

- Robinson Crusoe

- Oliver Twist asking for more

As well as allusions to specific texts, cartoonist utilise the following:

Slogans, sayings, proverbs

- ‘Beautiful one day, perfect the next’

- ‘Did the ground move for you?’

- ‘Too many cooks spoil the broth’

Familiar comic or mythic scenarios

- Painting yourself into a corner

- Using carrot on a stick to move donkey

- Lemmings rushing over a cliff

- Dole queue

- Cannibals’ cooking pot

Archetypes and stereotypes

- The smiling used car-salesman in striped blazer

- The hen-pecked husband in an apron

- The St Bernard dog with a brandy flask

- The knight in shining armour

Cartoonists also routinely make use of other current news events to make their point. Again, this involves utilising narratives and scenarios with which the viewer is already familiar. If not, the cartoon may well remain incomprehensible. Some years ago there was a bizarre and tragic incident in Nepal when a young member of the Nepalese Royal Family went berserk with a gun and killed other family members. Hardly the subject for a cartoon. The Australian cartoonist Nicholson transposed the scene to Buckingham Palace: his cartoon shows Prince Charles in army fatigues brandishing a submachine gun at the other British royals as they sit at the dinner table. ‘I’ve come to have it out about Camilla!’ he yells. (At the time Charles’ lover had not been accepted into the royal family.)

Hence cartoons rely heavily on intertextuality. They create meaning by exploiting the reader’s familiarity with the meanings of other texts and images.

Caricature

This is another important technique. It can be regarded as a resort to the trope of hyperbole but it should be noted that caricature in art is not always used for purposes of humour or ridicule. Conversely, cartoons do not always depend on the use of caricature. Caricature involves exaggerating one or more features characteristic of the person. For instance, ears slightly more prominent than usual are made huge. While this is often funny and in one sense involves a departure from literal truth, there is a sense in which caricature can get closer to what is unique about an individual than a straight portrait. Caricature is of interest to those who study the psychology of recognition. The principle even occurs in nature. If a male bird attracts the female by having a certain colourful pattern, a male who happens to have an exaggerated form of the pattern is likely to have better luck than most. Over time the characteristic will evolve to become more and more extravagant, as in the peacock’s tail (see Rhodes).

Caricature is about individuation. It can be distinguished from distorted depictions of supposed types (for instance the stereotype Negro or Jew); the term grotesques can be applied to these (Rhodes). Caricature serves the cartoonist by:

- identifying the persons in the dramatic scenario being presented;

- allowing simplification of the drawing;

- signalling that this is all about fun or satire.

Caricatures based on drawn or photographed images can be produced by computer software which computes the dimensions of facial features and the distance between them, compares the measurements to norms for the relevant population, identifies those that are furthest from normal, and then reshapes the image by pushing them still further from normal. Cartoon caricatures need not be based so closely on the actual characteristics of the person. Newspaper readers get used to the way a particular cartoonist caricatures a well-known politician. The current prime minister is portrayed with a grossly protruding lower lip. This seems more a cartoonists’ convention than an exaggeration of actuality.

Dialogue

Although modern cartoonists pride themselves on doing a lot without words, most use words very effectively when necessary. Like comedians, playwrights and screenwriters, they have a good ear for the idioms of colloquial speech. If they have a character saying something it is likely to both concise and ‘true to life’. The gag cartoonist Gary Larsen is a good example. Tom Tomorrow, published mostly in ‘alternative’ media outlets in the USA rather than the more conservative mainstream press, relies heavily on words but they are very well-chosen words.

The cartoon in the newspaper context

Cartoons are dismissed by some as ‘childish scribbles’ and it is perhaps surprising that these drawings of ‘low modality’ are given prominence in serious newspapers. (An example of an image with high modality would be a sharp photograph; it represents the literal facts of the world as fully and accurately as possible.) Actually, of course, cartoonists are highly skilled and there are good reasons why low modality is appropriate. Think of The Simpsons—it would be much more difficult for the show to play with ideas, explore different situations and parody well-known movies if the characters were played by live human beings. Compared to other genres and styles of graphic art, cartoons function more like words. As long as a signifier serves to establish meaning it can be simple, and indeed arbitrary. If I want to indicate that someone is all alone in some respect, I can call him ‘Robinson Crusoe’, referring to the archetypal isolated man. The cartoonist would draw Robinson Crusoe, with his long beard and crude goatskin clothes marooned on his desert island. An elaborate drawing would be pointless and distracting. All that is needed are a few lines to establish the concept ‘Robinson Crusoe’. As with words, convention plays a vital role. Words only work because everyone agrees about what they mean. There would be no point in trying to draw a more original Crusoe or one that more accurately reflected the way he is described in the novel that first created this character. It has to be Crusoe (or Elvis or Moses or whoever) as conventionally drawn in this society at this point in time.

It is still the case that every cartoonist has a distinctive style. Nothing is more expressive of individuality than the freely drawn line; we identify individuals by their signatures (Hatcher p 77). This distinctiveness helps to mark the cartoon as something that reflects the opinion of one individual, not necessarily that of the editor or owners of the newspaper. The simplicity and exaggeration of the cartoon establish it as a space of play or fun in contrast to the more sober articles and editorial columns. I would argue that the intertextuality of the cartoon, its borrowings from folklore (fairy tales, current movies, celebrity gossip, other news events) also mark it as a site of popular culture within the op-ed pages of a serious upmarket newspaper. In a way, it is a site where ordinary people get to have their world displayed, pushing aside for a moment the world of powerful men in suits.

The cartoon as polemic

But how effective are cartoons as a means of persuading people to accept a particular point of view? There is some evidence that (like editorials) they may help confirm a reader’s existing point of view but are unlikely to change it. Cartoons mostly deploy satire, which means holding some person or group up to ridicule. Satire means doing more than merely criticising or hurling abuse (that is called invective); satire requires some imaginative transformation, some fictional departure. The criticism acquires more force because the reader or viewer has to participate in some way, ‘decoding’ the fiction to understand the point. A famous literary example was Samuel Johnson’s denunciation of the English for allowing a famine to rage in Ireland in the eighteenth century. He proposed that since there were too many mouths to feed in Ireland an excellent solution would be for Irish infants to be imported into England as food. He pretended to adopt the position of those comfortable with exploiting Ireland and took it to a ludicrous extreme. His point was that people in England, who ate food grown in Ireland where the poor could not afford to buy it, leading sometimes to death, were morally no better than cannibals. But some readers failed to decode the satire, they thought his proposal was serious!

We have already seen how the very nature of the cartoon—a drawing produced at short notice and intended to assert a proposition about current events—almost demands some departure from literal representation of the world. The medium is thus perfectly suited to satire. It is sometimes asserted, though, that in recent times cartoonists have tended to settle for easy targets and cheap humour rather than more penetrating critiques. Also, because they enjoy caricature and want a dramatic scenario involving people, cartoons tend to be preoccupied with the doings of well-known politicians—as opposed to background influences, long-term trends, wider political forces—but this is typical of the news media in general.

Cartoons depend on the imaginative involvement of the reader. This is part of their appeal. It means that there will be a range of different interpretations and reactions. Take the Prince Charles cartoon referred to earlier. Some might regard it as tasteless, exploiting the Nepalese tragedy for cheap laughs. Others might see it as implicitly offering some consolation to the Nepalese: ‘look, our royal family is also dysfunctional’. It is also the case that on a given day, not all readers will be able to make sense of the cartoon in their newspaper (Hatcher p 77). Either they are unfamiliar with its intertextual references or it is too subtle to decode. Still, the ambivalence of the cartoon (as with other satire generally) protects it to some degree from the wrath of those who might want to censor it. ‘Oh, is that how you interpreted it?’ the satirist can say, ‘I didn’t mean anything nearly so extreme.’ In totalitarian regimes cryptic satires have often been the only vehicle for the expression of dissent.

Future trends

The future of the cartoon as we have known is bound up with the fate of newspapers and other printed periodicals. My own view is that in the online environment, where the reader has to choose to follow links to the day’s cartoon, some of the impact of the cartoon as a lively and unruly presence on the page is diminished. Again, if in future the custom will be to print out just those sections of the paper one particularly wants—news, business, sport—many will miss the cartoon. The present mass audiences for news periodicals will probably be replaced by market segmentation: diverse online offerings catering to a diversity of tastes. While loss of the cartoon as a sort of public domain in which cheeky dissenting views are expressed is to be regretted, the web potentially allows many more cartoonists to display their talents—and to be less restrained by editors. Mark Fiore is a cartoonist who has abandoned hard copy and works entirely online; he welcomes the opportunity to create more elaborate cartoons that exploit sound and animation.

Conclusion

Cartoon art is used for many purposes, including illustration and advertising. The focus here has been on the editorial cartoon because of the particular challenge in using images for polemical purposes, that is, to engage in political debate.

Cartoons have a long history in the print media. They were fostered by the allegorical character of medieval art and the Renaissance development of caricature. To overcome the problem of the ambiguity of images (we can see it but what does it mean?) cartoons normally involve some trope. There is some embellishment or transposition of--or other departure from--literal facts. This is just what satire, in any medium, also demands. In making connections with other familiar texts and images they rely on intertextuality, endlessly recycling the motifs of popular culture

References and Further Reading

Carl, Leroy M. (1968), ‘Editorial Cartoons Fail to Reach Many Readers’ in Journalism Quarterly, 45:533-35.

Carrier, David (2000), The Aesthetics of Comics, University Park, PA, Univ. of Pennsylvania Press.

Day, Anna (1999), ‘Australian editorial cartoons: Is there a change afoot?’ in Australian Journalism Review 21 (2): 117-33.

Edwards, Janis L. (1997), Political Cartoons in the 1988 Presidential Campaign: Image, Metaphor, and Narrative. New York & London, Garland.

Hatcher, Evelyn P. (1974) Visual Metaphors: A Methodological Study in Visual Communication. Albuquerque, Univ. of Mexico Press.

Hess, Stephen and Sandy Northrop (1996), Drawn & quartered : the history of American political cartoons. Montgomery, Ala., Elliot & Clark.

Lester, Paul Martin (1995) Visual Communication: Images with Messages. Belmont, Wadsworth.

Phiddian, Robert with M. Bramwell and A. Roe (1998), ‘Tweedledum and Tweedledee: Political Satire in the 1996 Australian Federal Election’ in Meanjin 57/2: 278-98.

Rhodes, Gillian (1996), Superportraits: Caricatures and Recognition, Hove, Psychology Press.

Shikes, Ralph E (1969), The Indignant Eye: The Artist as Social Critic in Prints and Drawings from the Fifteenth Century to Picasso, Beacon Press, Boston.

-----------------------

The lecture was prepared by Dr Andrew Wallace CQU Gladstone